Text / Shanyu Zhong

Transgression after Transgression

- Artist:

Text / Shanyu Zhong

A question commonly asked does not promise an answer as expected. “Why would a female artist paint muscular men?” Shang Liang is countlessly thus asked and expected to give the textbook reply – to objectify men. On the contrary, she is astoundingly at home with the fascination she projects onto these youthful, full-blown bodies. “His appearance embodies all the qualities that I appreciate. I wish someone like this really did exist, be it in me or others. It’s the body of an idol.” An idol implies idealization, something higher than reality. Before the viewer’s eyes even touch upon the “perfect” muscles, their images have already been exalted by the title of the paintings.

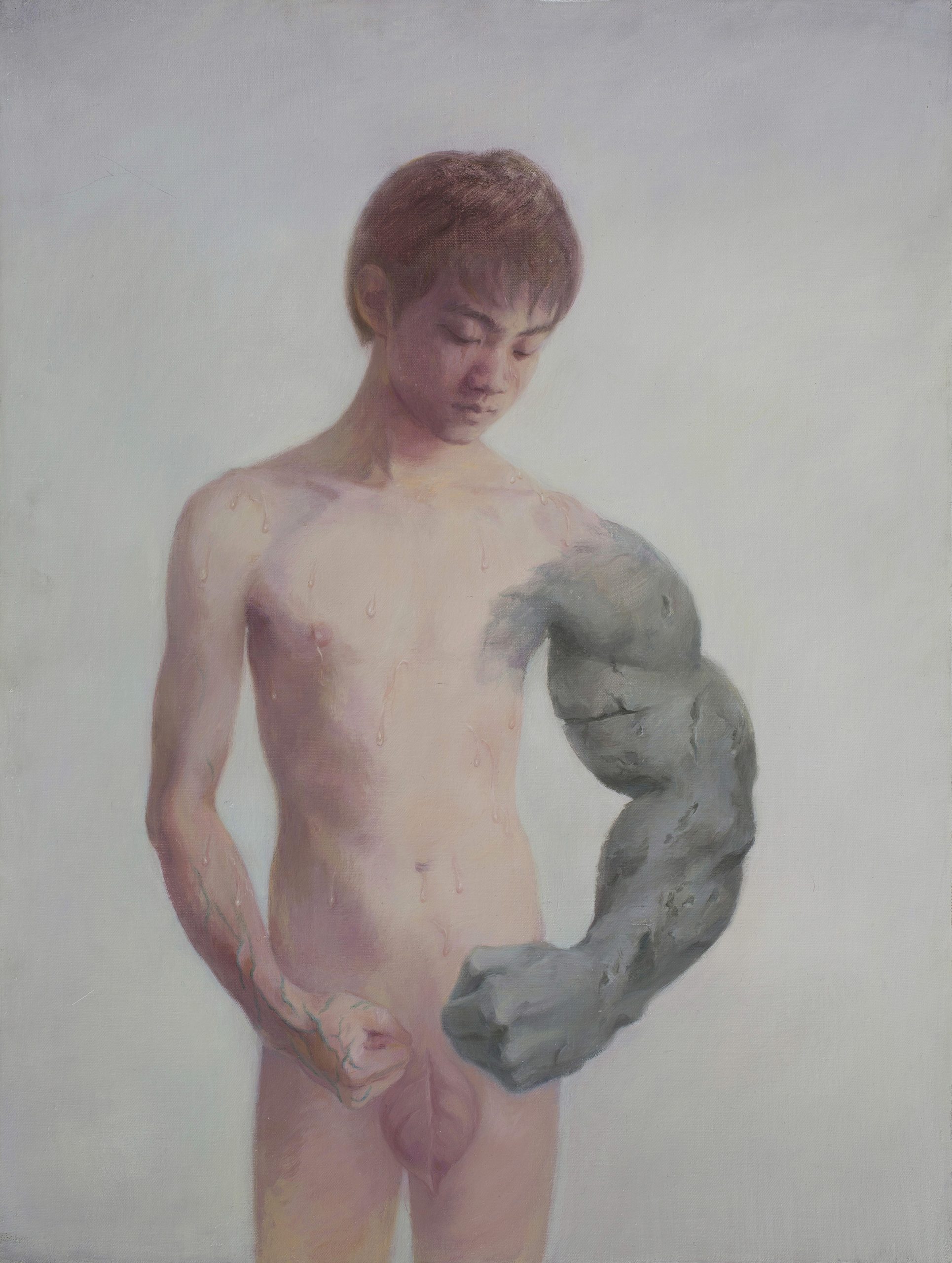

What is “real” in “The Real Boy”, or “good” in the “Good Hunter”? In the former series created during 2012 and 2016, grounds of ethics are given by the innocence of the face and the original frailty of the body, along with the classical fig leaf that enables us to whitewash voyeurism as a righteous gaze. The title drew inspiration from a music box Shang Liang acquired from an antique store in Hong Kong: it was signed on the bottom as “正道仔”, which literally means “boy on a correct path”. Out of the pseudonym of an anonymous man, Shang Liang imagines a timid youth begging for forgiveness, yearning for the “correct path” yet unable to picture himself on it.

If frailty is taken as a symbol of virginal purity and virtue, the muscles, highlighted and sexualized as they are, must be sinned. But is it the artist’s intention to make her characters confess? Rather, ethics has not only attired them but also fettered them within the Garden of Eden. And now purity is forsaken! “The Real Boy” is ready to venture: in 2014 he is half dressed in a shirt, yet unaware that this would be his last time seen with garment. Soon after he sweats, grows hair, and commits the first transgression of ethics by desire – hands swollen as boxing gloves tell of inflammation, while the petrified arm clearly falls victim to Medusa’s vicious gaze.

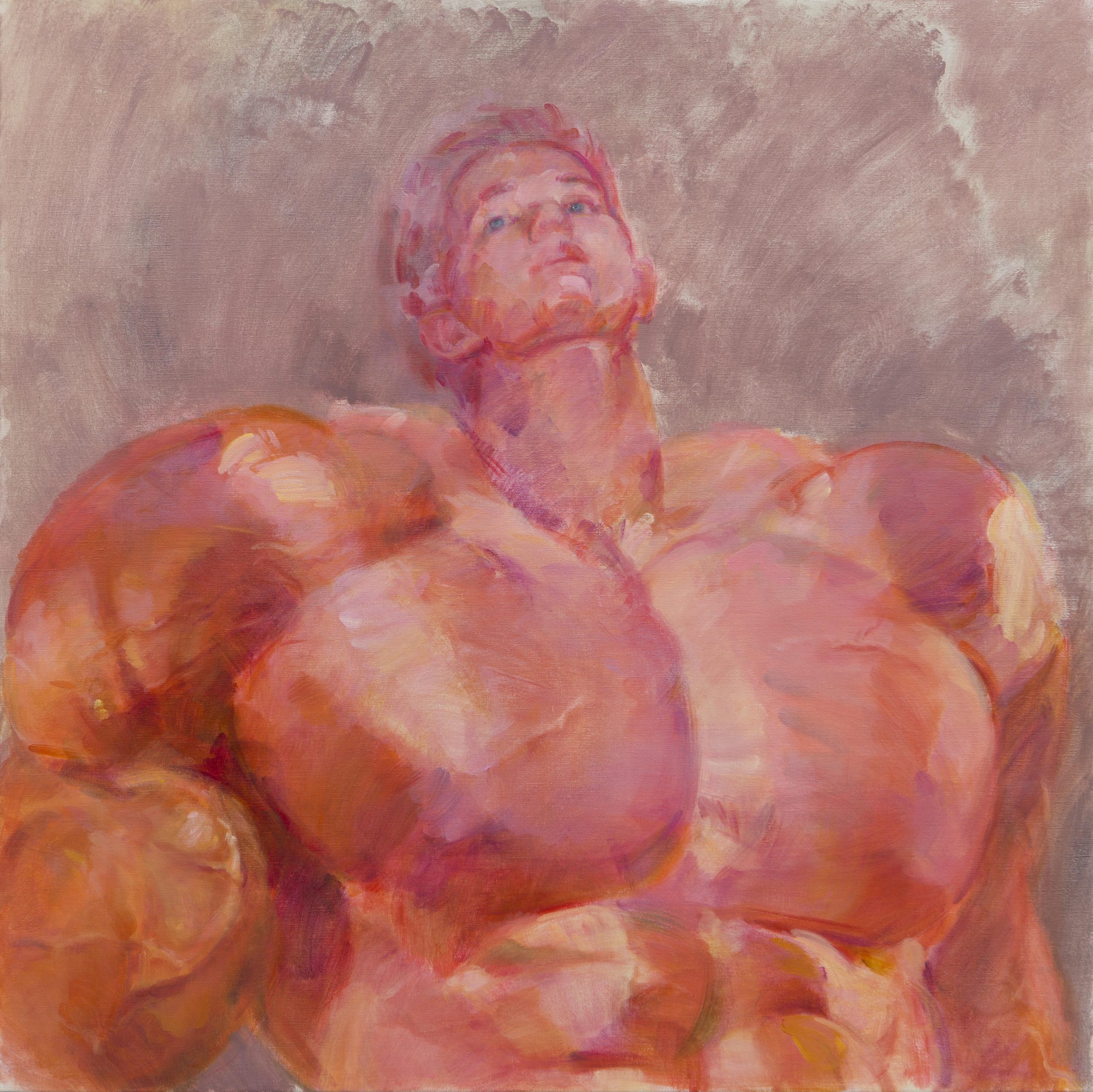

By 2018 when the “Boxing Man” series started, the ethic “world of project”, a term coined by Georges Bataille, has been completely eroded by the erotic body. Flesh, blood, skin, and tissue fluid merge into a whole against a coral pink background. Such imagery is not uncommon in art history. Several of Michelangelo’s unfinished sculptures, for instance, depict vague human figures struggling to take shape out of boulders, only to be eventually consumed. A more apt comparison in form would be Umberto Boccioni’s futuristic masterpiece Unique Forms of Continuity in Space (1913), in which muscles, deformed as a result of high speed, seem impatient to break away from the body and rush into the future – of course, the fascist future it later became involved in was nothing to boast of, and the vigor and energy the work embodies was soon cast aside after the War.

Compared to the Boccioni sculpture covered in a black sheen, Shang Liang’s two-dimensional “muscular men” seem sluggish, rendered painterly by relatively curt and crude brushstrokes. In the “Good Hunter” series, the artist repeatedly depicts a figure en face that resembles the tough-guy hero appearing in slow motion towards the end of a film. The figure leaves the past in a hazy backdrop and faces a future that will soon be disrupted. Such a hero, or rather a stereotype in the film industry, can but remain silent at the end and walk towards the audience, even as the body’s kinetic energy and emotions both reach the pinnacle; in their place is repetition and restoration, signaling a return to basic human actions. More comparable in terms of performativity to Shang Liang’s pictures is the fashion runway – particularly, those post-1980s when the age of the supermodel has waned, and both smiling and swaying have been prohibited. The new models exude sexiness without appearing overtly sexualized, therefore exactly Shang Liang’s “new man”. The body’s internal strength is dissolved in a uniform rhythm and a homogeneous space, and turns into a neutral container for the skin/clothes. In short, one may not use their body, except for walking.

In such an attempt to conceal strength, we almost witness a timid artist aspiring to sublime the sexualized body. In Good Hunter No.8 (2018) and Good Hunter No.11 (2019), the artist creates a caricature-like character, someone “in between a star bodybuilder and a dancing boy, an action cut a section off of”, and admits that his face may inadvertently reveal qualities of a self-portrait. But if seen in the realm of self-portraiture, the slightly backward leaning character is apparently somewhat out of place with his (or her?) eyes wandering and dazzled, staring out of the frame. This is a narcissist not to dally with, who not only exhibits no intention of communicating with us, but also attempts to thoroughly exclude us. It is here that Bataille’s sacred space of eroticism appears. Just when the sense of shame buries desire deep beneath, the taboo induces the all-daring transgression by desire. This instant of non-reason may well compare to the ecstatic moment when heavens were opened and Ezekiel saw visions of God.

The portrait’s hopes of excluding others now seems to be dashed. “New Order” implicitly connects the dominator and their subjects, and the “Good Hunter” always seeks for their prey. In such a concealed relationship of submission lies the second transgression of ethics by desire. Shang Liang admits being a fan of boxing games and martial arts movies in childhood, imagining herself as the perpetrator of violence – of course, these are forms of unabashed violence. In parallel, subcultures are gradually incorporated into forces of mainstream culture nowadays. An example would be Sandee Chan’s 2022 album Discipline, which deploys BDSM as a metaphor for politics, media, and other social issues. Similarly, fashion brands that extol fetishism and bondage, like Mugler, are now back in trend after normcore has passed its prime. They tease and provoke and are then summarized as high-sounding concepts in fashion show notes – these are forms of unabashed eroticism.

Not unlike runway models emerging from the vague backstage, Shang Liang’s “muscular men” step onto the stage of art one after another; or rather, her pictures function as storyboards of an animation or comic book, ranging from hasty scribbling and at others delicate close-ups (despite the artist’s claim that “caricature is much more exaggerated than contemporary art”). Their coherence in imagery suggests that each of her works, far from being isolated, act in concert to fulfill a narrative, albeit a somewhat hollow one. Not only is the hazy background non-referential to any specific era or region, but even the muscles are good-for-nothing, “turning into an overstated symbol that exists for the sole purpose of showing his gallantry, forming a conditioned reflex like the thought of bondage at the sight of a choker.” The picture is neither partially concealed, nor is the character half-resisting; the scene with everything to see is nevertheless devoid of anything to see; in the overflow of symbols lies the barrenness of meaning. Such images may well be the consumer goods of desire that are disposed of instantly after desire is gratified, leaving nothing behind.

Another symbol serves as a more straightforward testament to the disposability of Shang Liang’s images: a Pinocchio-like character appears in “The Real Boy” series, whose long, sharp nose pricks the arm like a syringe; in some works, Pinocchio’s heads pile together like discarded human-shape syringes. (Now, what’s Pinocchio’s lie? How unnerving.) The experimental series “D520C”, created in 2016 and based on the artist’s sketches unconsciously made while traveling or talking on the phone, further develops the character. Against a gradient, metallic-colored background, the pointed nose is subconsciously morphed into impromptu, broken, and radiant lines. Together with the shrunken muscular man, logo of Nike, and diamonds, the imagery of the nose makes its appearance felt before bursting apart at the corners of the picture, reinforcing the interlocking of drug, commodity, and desire. As Paul B. Preciado points out, the “success of contemporary technoscientific industry” has managed to transform “our depression into Prozac, our masculinity into testosterone, our erection into Viagra, our fertility/sterility into the Pill, our AIDS into tritherapy, without knowing which comes first: our depression or Prozac, […] tritherapy or AIDS.”[1] Human beings’ subjectivity has fallen under the control of pharmacopornographic capitalism, whose products include serotonin, antibiotics, alcohol, tobacco, cocaine, morphine, and oocyte cryopreservation.

As a cisgender woman, my rejection of chunky muscles as a teenager had its origin in a photo of female bodybuilder Chris Wesenberg in my biology textbook, showing her extremely low level of body fat. It was only years after that I learned that women are born with lower testosterone levels than men, making it harder for them to grow muscle. The almost alienated, even terrifying state of muscles relies not only on highly intense body training, but also on steroid drugs commonly used by men and women alike in bodybuilding contests. Which comes first, the flawless muscles or steroids? In Shang Liang’s work Pharmacopornographic capitalism quietly injects the question.

Long before I realized the “sex” of muscles, Shang Liang discovered during adolescence that she could no longer beat boys of her age. This might have marked the inception of her gender consciousness, while serving as the catalyst for attributing her instinct of “painting masculine muscles” to this long-standing fear surrounding physical strength. Since the characters’ strength has far outgrown that of the painter herself, she finds herself unable to wield the same willfulness as her male counterparts when dealing with similar motifs — willfulness is always perceived as masculine and connotes sexualized power. Instead, she can but distance herself from the figures and obscure their character, “permeating long histories and vast dimensions, comingling various figures to produce something out of the blue.” In Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray, the protagonist stays young and beautiful by letting his portrait bear his own aging and evil. The picture eventually becomes the remaining evidence of his crimes and induces his death. Were it not for the innocent or hazy face of Shang Liang’s muscular version of Dorian Gray’s portrait, were he not moral, healthy, or heroic, were his useless strength to be released as violence, he would pose a substantial threat to the artist.

In fact, such violence has found itself uncontainable in the work of not a few artists. Speaking of Francis Bacon’s paintings, Deleuze painstakingly highlights the chunks of flesh in spasm, the overflowing pinkish liquid, as well as figures hysterically screaming, limbs rising and falling, organs diastolic and systolic… In her works, Shang Liang shares a certain abjection with Bacon. She distances the respective appearances of flesh and body to such opposition that the frail body can in no way bear the weight of the well-built flesh. While the figure maintains a smile, the body has nonetheless banished the muscle out of its territory. In other words, the muscle no longer resides within the interiority of human beings and has instead turned into a preposterous outer casing, an abject incompatible with the rational self.

While Bacon favors a muddled animality, Shang Liang consciously constrains her characters within the scope of classical portraiture. By drawing on the Egyptian and Greek paradigm of the kouros, she elevates humans to demigods and lets ethics regain the upper hand. The pictures exude “qualities of nun portraits” – the artist’s use of such a highly sexualized and religious description reveals prudence and self-protection in her work. She makes these men walk, sit, and think within preexisting rules, thus leashing and redefining masculine power (even if this may not have been her initial intention). The male body is judged, disciplined, and even rendered abject, thus reversing the active-passive relation between the male painter and the female model in art historical conventions. Shang Liang is almost peremptory in this regard: if the (male) object is discontent with his passive status, if he shows any longing for agency or request for an existential context, he does not deserve the label “good”!

In recent years, Shang Liang has further rejected pictures that seem overly lifelike and tantalizing. Repeated depictions have almost turned muscles into a monochromatic landscape and made the flesh inseparable from its smooth protective gear in a cyborg-like form. The artist grasps the resonance between her creative tendencies and social aesthetics at large, both being “refrained, indifferent, icy, sleek, not arousing any emotion”. If a comeback of the tantalization may still be said to manifest from pictures covered largely in red, orange, or purple, then “Sofa Man” (2018-2022), a series of sculpture made of fiberglass or aluminum, presents a thoroughly smooth body. Two muscular men sit seamlessly side by side with hollowed faces that can be infinitely supplanted, which spells the disappearance of the self that banishes the muscle out of the body’s territory, leaving behind merely an empty (but thick) outer casing. We can almost imagine how the casing is used as a photo prop, self-reproducing within social media while harvesting likes. This is precisely the direct outcome of what Byung-Chul Han calls “the sleek”, a concept whereby “one is seized with a kind of haptic ‘compulsion’ that makes one want to touch or even suck on them [the smooth sculptures].” Dirty porn is out; obsession with hygiene is in, desire slick as Brazilian waxing.

On the other hand, the overly sleek and healthy is as unnatural as a plastic mannequin, lacking negativity to a morbid and lifeless degree. As blood runs quick and vessels swell wide in bodies well-developed to their zenith, the fleshy frenzy is, unfortunately, in no way enchanting or intoxicating. What overwhelms us, then, is a destructive threat and fear, which ultimately leads to the one concept farthest away from Shang Liang’s works: death. Admittedly, it’s cliché to consistently attribute artistic practice to childhood experiences, but for Shang Liang, the body and death are indeed familiar motifs since childhood. She used to peek at the anatomy books of her mother working as a medical doctor, and was also impressed with the bird specimens she made as a student for an extracurricular biology group. The pleasure and fear of death seized her simultaneously.

Shang Liang obviously does not depict death per se, though her abnormally well-built bodies are strained to the extreme. If we recall what high hopes the artist places on these bodies, seeing them as the perfect idol, we shall find the word “idol” bloodcurdling. We are reminded of the celebrities dying young in Elizabeth Peyton’s paintings, whose good looks exist for but an instant and are infinitely survived by symbols of the idol. Unlike Peyton, Shang liang’s subjects are almost always anonymous, except for Hemingway in the “Good Hunter” series, who died a rather fierce and masculine death. It is the fluidity of identity that “keeps fresh” their bodies and renders inconspicuous their vulnerability. Nevertheless, death is always discreetly lingering around the bodies. Within the contradictions between the erotic and the sacred, within the strength tightly held back by the artist, desire is eventually pushed to the edge of death. This is the last transgression of ethics, which will remain the unsayable secret of the youthful and full-blown bodies.

[1] Paul Beatriz Preciado, Testo Junkie: Sex, Drugs, and Biopolitics in the Pharmacopornographic Era (New York: The Feminist Press, 2013), pp.34-35.

Originally published in Art-Ba-Ba (2023)

Revised and included in Shang Liang: New Man (exhibition catalogue, 2024)