Text / Ken Adams

Shang Liang: Newman

- Artist:

Put simply, in the humanist age, Pinocchio wanted to become human; in the so-called post-humanist age, humans aspire to become Pinocchio. In so doing, we attempt to internalize an imaginary other. There was once just the doll, now we wish to become that doll.

Adam Geezy, The Artificial Body in Fashion and Art: Marionettes, Models and Mannequins

Appropriating Weston’s style, Mapplethorpe puts in the place of Weston’s child the fully sexualised adult male body. Gazing at that body, we can no longer overlook its eroticism. That is to say, we must abandon the formalism that attended only to the artwork’s style.

Douglas Crimp, The Boys in My Bedroom

But there was no longer much talk about fashioning a “new man” who would guide the nation into a brighter future.

George L. Mosse, The Image of Man: The Creation of Modern Masculinity

I.

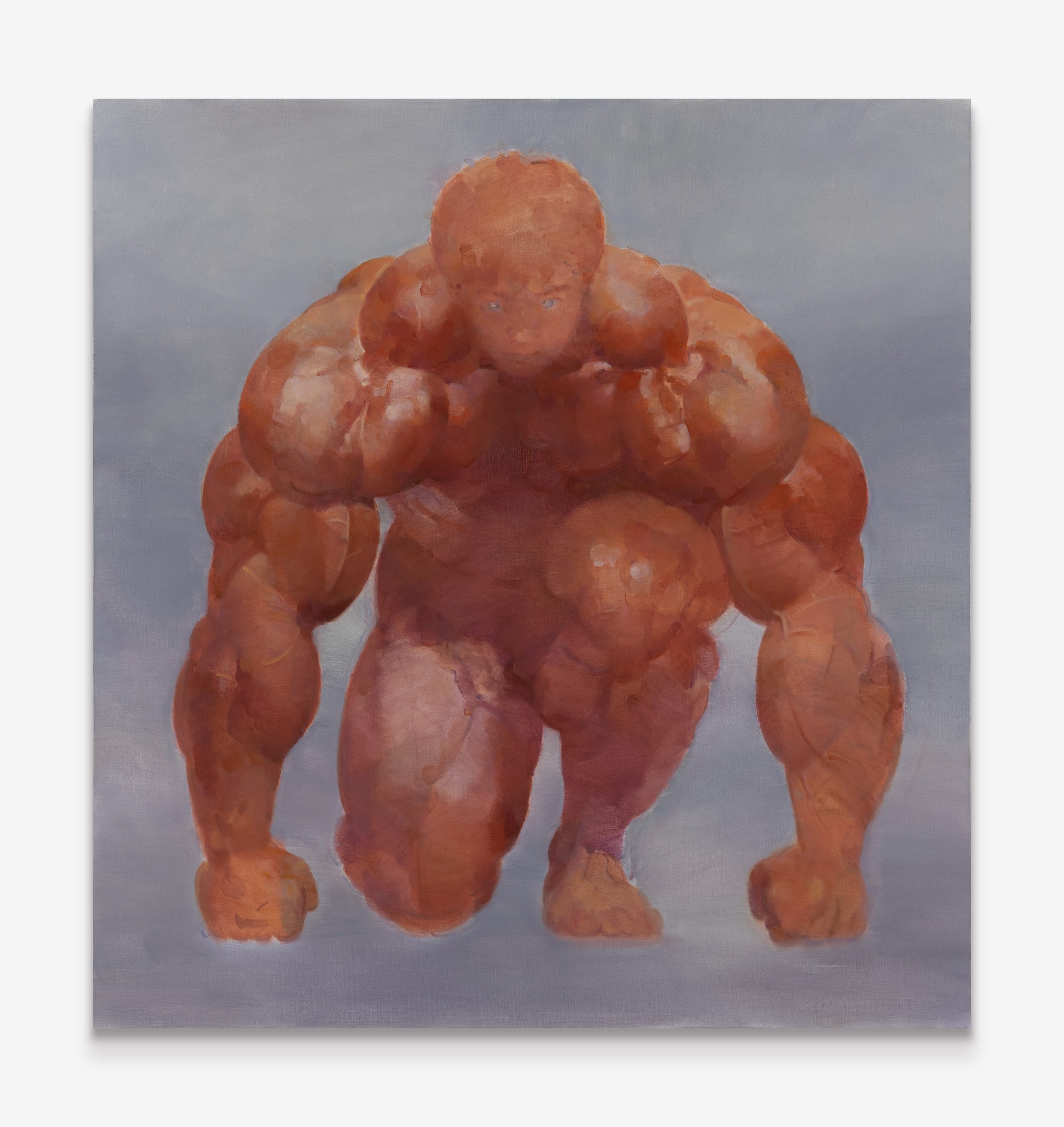

Let’s start by tentatively unscrewing the heads of Shang Liang’s hunters and boxers (if, as we would have assumed, there are more than one hunters and boxers, in relation to the theme of the recent exhibition that concerns us, New Man: it is about abstracting, extracting the essence of such new men, instead of demonstrating disparate manifestations of one single man), before reconnecting the faces back to the bodies, that are in turn attached to finger-pointing, stiffly erect hand-guns, or, just as well, clenching and hard swollen gloves that palm possibly nothing but its own tight, dry contraction: men—armoured, equipped and geared as cyborgs proper—apply heavy make-up on their faces, and therefore no longer look like who they are. There is something facial, cosmetic and weightless about it, against the chunky, overbuilt body and the indefinite, gaseous background. It is obvious that the same or at least similarly heavy make-up is also applied on their antigravity bodies of vascularity, so that each one of them appear to be a whole and can therefore be identified as such (the ochreous hunter, the black hunter, the golden hunter, and so on), but the faces do not stand as metonyms—the bodies are irreducible to the faces that do not look like themselves and look like each other. The anti-Schiele and even anti-Saville bodies are appendixes, un-screwed. We suspect that we are looking at caricatures and masks. Benjamin H. D. Buchloh: “…both caricature and mask conceive of a person’s physiognomy as fixed rather than a fluid field; in singling out particular traits, they reduce the infinity of differentiated facial expressions to a metonymic set. Thus, the fixity of mask and caricature deny outright the promise of fullness and the traditional aspirations toward an organic mediation of the essential characteristics of the differentiated bourgeois subject.”[1]

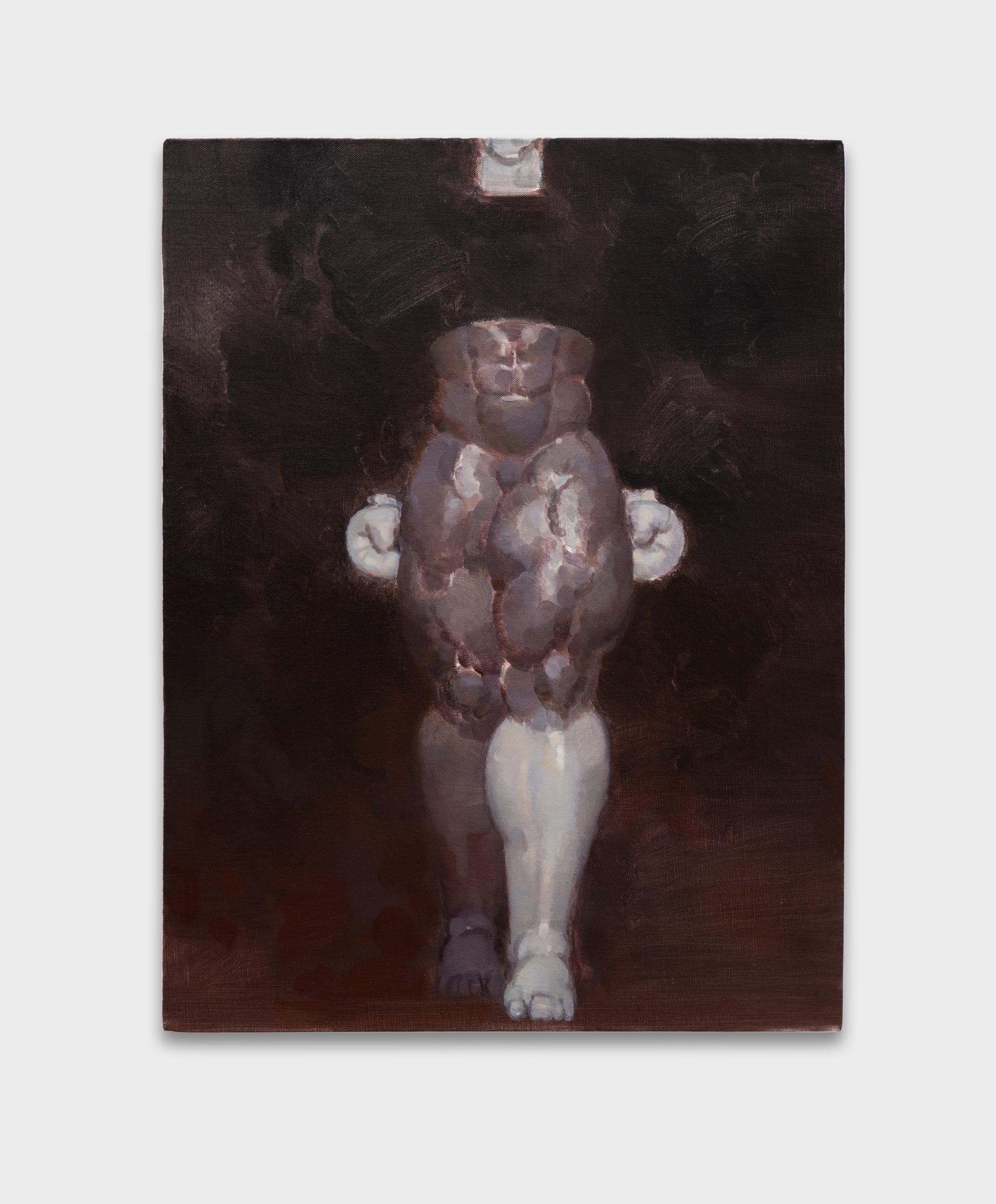

Take the smaller painting Boxing Man No.15 (2021) from the New Man exhibition as an exception, a counterexample. It includes an unidentifiable face halved by the frame of the picture, hovering above a partially concealed body (in amusing contrast to Good Hunter No.3, 2018, which depicts merely the torso and fractured arms). The face is reduced to a chin attached to a thick, spineless neck; the plump chest muscles and strong arms are also invisible, smeared and covered. This is for Shang Liang an unusual treatment, because the penis-less hunters and boxers in painting are better known as totally and flawlessly built men, hunters and boxers who are essentially bodybuilders, since they are not generally seen in hunting or boxing scenarios. The cherry on top, that is, the face, is in most cases cute, boyish and ageless, anything but a bodybuilder’s face, which is subject to various changes such as permanent enlargement of bones when Human Growth Hormone (HGH) is used (or a boxer’s, for that matter; it is simply too impeccable). So total and flawless, the bodies have to meet the viewer en face on many occasions, as if walking towards the viewer or striking an un-flexing, modest pose, just to give a view as comprehensive as can be. The effaced boxer man in Boxing Man No.15 takes a rather unnatural walk, with his two hand-gloves floating rigidly by his thighs. But even more unnatural and unusual is that different, contrasting colours are used on the body, emphasising in grey the invisible face, the bulging gloves and one of the legs. This particular chest-less, penis-less boxer, therefore, matches his gloves and leg with his face, which is whitened atop a black, glossy, partialised body. He is tentatively beheaded, at once out of focus—we cannot decide, as in other paintings, how or where does he direct his gaze—and in focus—demonstrating exactly which parts of his body should be eyed.

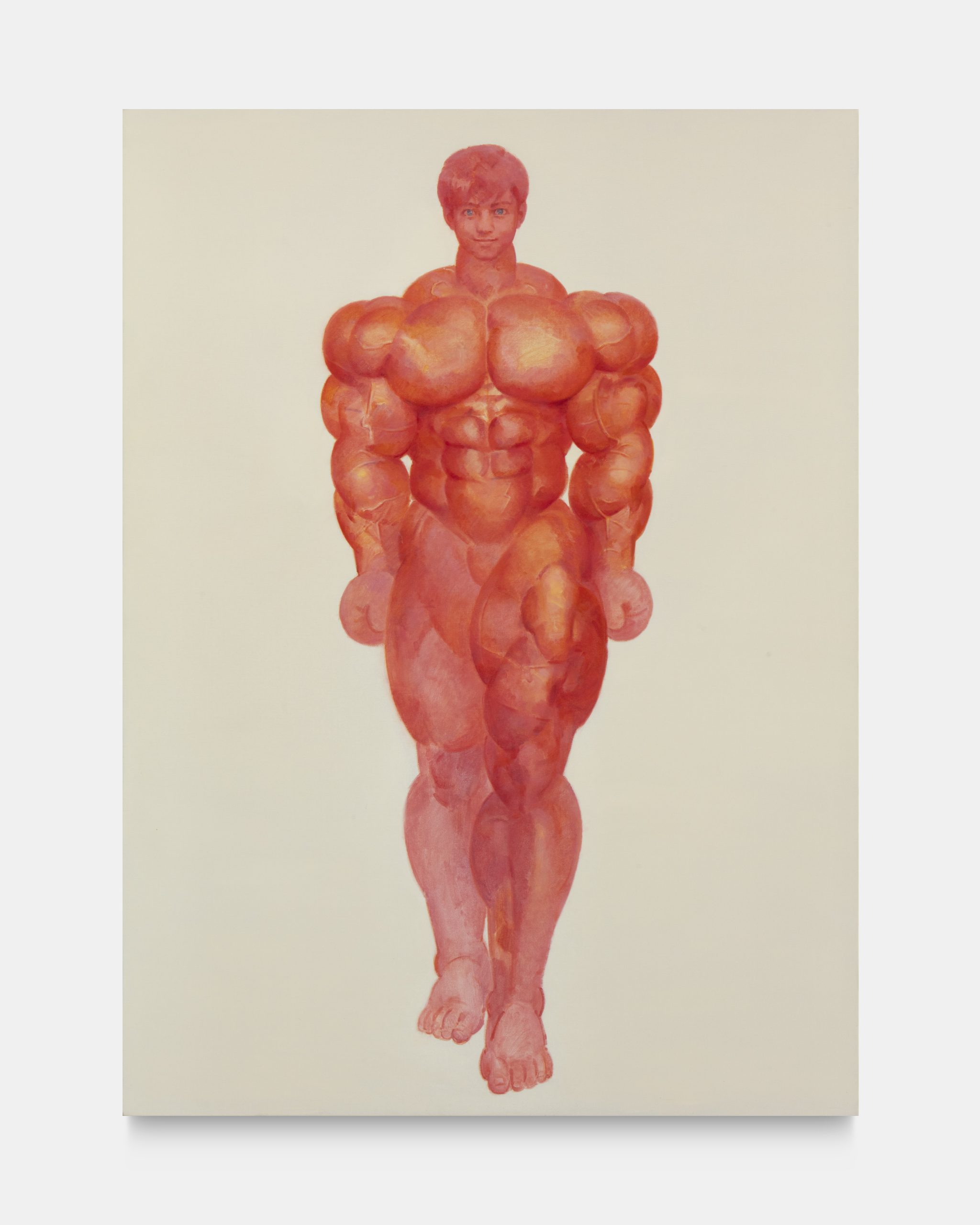

This tentative unscrewing is provisional yet imperative, because how is the face linked to the body in time, is of significance here. The sitter’s face in many of Shang Liang’s paintings is unmistakably Asian, Chinese. Even Japanese, resembling a kind of anime androgyne, or an Asian ephebe. Unlike a previous suite of paintings and sculptures in which the figure rather abruptly yet reasonably becomes Ernest Hemingway (Good Hunter No.5-No.7, 2018), to whom Shang Liang had made a number of interesting allusions over the years (gloves and guns), the paintings in the 2022 New Man exhibition all feature beard-less, wrinkle-less, muscle-less and sometimes featureless faces (we were saying there is something cosmetic about it; now we also recognise the inherent plastic aspect of it, a different, extreme kind of Ken doll), readily present as weaknesses and invulnerabilities. This is perhaps the only visible part of the man that remains untrained, unstrained, unchanged and by extension un-timed, especially in those paintings where the face is strangely yet aptly hollowed—not only un-timed, but also un-spaced. A kind of superhuman training can turn the hands into stiff guns or puffy gloves; just as uncanny or even more so, are the faces that stay the same, rejuvenated, age-less, like the face of a 15 years-old boy, barely covering with a bowl cut of lush, casually textured hair the innocent eyes that are sometimes filtered by blue, green or red contact lenses. How can a portrait of a naked young boy be justified today?

(Un)naturally and inseparably juxtaposed with one another, the face racialises the body, albeit minimally—the only aspect that prevents it from being conveniently asian is but the ever-changing skin tone—and burdens him with a heightened sense of time, rendering the face-body relationship an anachronistic one. Other examples that temporally distance the face from the body, are paintings like Good Hunter – Duplicate No.2 (2022), where the boy’s face is protruding ahead of his superhero-landing body, gazing out aggressively. In earlier paintings like Good Hunter No.12 (2020), where, once again, the boy is striking a rather tensed, shy pose, one gets to have an even better look of the face.

In Good Hunter No.12, he smirks. Possibly toothless—in stark contrast to the inanimate objects that grin in The Split Self No.1 (2022) and The Split Self No.2 (2022)—he gives a mostly uninhibited smirk, occupied only and strongly by a hubris regarding himself, particularly his physique. The smirk is, despite the elongated neck that un-buries the face from the bulging shoulders almost as much as in Good Hunter No.15, what brings the face back to the body, in one way and another: the timid, toothless smile teams up with the hand-gloves that are embarrassed by not having any pockets, and is pleased with its own body, looking directly into a mirror. This boy’s self-identification, self-appreciation perhaps is what drives me, a face lover, away from his babydoll visage, which is arguably more casually (reads: more masterfully) depicted (again, a caricature or a mask), to the chiselled body.

II.

Jessenka: “I was about to get showered, I looked in the mirror and I have never looked so good in all my life. I had a big smile just come across my face, and I flexed my abdominals and my obliques in the mirror and they all stood out like three or four fingers. All of my abdominals are like chocolate biscuits and I just smiled at me in the mirror . . . I felt confident, I looked fucking tremendous. That sounds really arrogant doesn’t it? But I did. I felt tremendous, I felt full, I’d got my carbing right, literally spot on the bone. I was ripped to the bone and hard and full . . . I felt like I’d won it before going on stage.”

Andrew C. Sparkes, Joanne Batey and Gareth J. Owen, The Shame–Pride–Shame of the Muscled Self in Bodybuilding: A Life History Study

He who denies morality is not abject; there can be grandeur in amorality and even in crime that flaunts its disrespect for the law-rebellious, liberating, and suicidal crime. Abjection, on the other hand, is immoral, sinister, scheming, and shady: a terror that dissembles, a hatred that smiles, a passion that uses the body for barter instead of inflaming it, a debtor who sells you up, a friend who stabs you…

Julia Kristeva, Approaching Abjection

To the body then. George L. Mosse’s opening line in The Image of the Man: The Creation of Modern Masculinity: “Distinct images of masculinity—the way men assert what they believe to be their manhood—have been all pervasive in Western culture.”[2] Flagging these images of masculinity as a Western phenomenon—prompting us once again to be mindful of the cultural, racial gap between the Eastern, juvenile face and the globalised, worn body—he talks about the unity of body and soul: “Masculinity was regarded as of one piece from its very beginning: body and soul, outward appearance and inward virtue were supposed to form one harmonious whole, a perfect construct where every part was in its place. Modern masculinity was a stereotype, presenting a standardized mental picture, ‘the unchanging representation of another,’… Such a picture must be coherent in order to be effective, and, in turn, the internalized visual image, the mental picture, relies upon the perception of outward appearance in order to judge a person’s worth.”[3]

Mosse also speaks of gymnastic exercises, which directly concerns our discussion of freakishly buff men in Shang Liang’s art: “Winckelmann himself had written about the Greek gymnasium where gymnastic exercises demonstrate the manly contours and sublime beauty of the naked male body. The rise of gymnastics as a means of steeling the human body was a vital step in the perfection of the male stereotype and came to play a leading role. The fit body, well sculpted, was to balance the intellect, and such a balance was thought to be a prerequisite for the proper moral as well as physical comportment.”[4] In different chapters, Mosse repeats the import of the unity between body and soul, in parallel with the unity (or lack of it) between body and face being forged here. He cites a counterexample written in 1810 of a known homosexual, who failed approaching the manly idea of beauty: “His nose and forehead signaled strength and daring, but the eyes were clouded and the lower part of his face was that of a feckless youth.”[5]

To be sure, Shang Liang is not alone in depicting and exploring human bodies that are built and carved. Jörg Scheller’s 2021 article Are Bodybuilders Contemporary Artists? in Frieze mentions a number of artists who have worked on the subject. A couple of instances include Polish artist Thomas Buck, who carves crouching bodybuilders out of soap bars; Argentine-Israeli artist Mika Rottenberg who for her 2004 film Tropical Breeze collaborates with bodybuilder Heather Foster; and Hannah Black, who in the 2015 film Bodybuilding “juxtaposes images of sculpted bodies and architecture, punctuated by text overlays: ‘Please help: my body refuses to grow/change!!!’ and ‘I follow plans to the end and still no gain’.”[6] Although the ambivalent, more-man-than-woman gender identity of Shang Liang’s characters would bar the artist from participating in an exhibition such as Picturing the Modern Amazon at the New Museum in 2000, one can without much difficulty consider Shang Liang’s practice in relation to works by Nicole Eisenman, Nancy Spero, Andres Serrano, and Matthew Barney, among others.

But something separates Shang Liang’s naked young boy from others. Something wrongs its time. We are to continue dwelling upon a fission in Shang Liang’s paintings, where it reveals its Achilles’ heel, the locus where it becomes fragile and may inadvertently or willingly break: that between, indeed, body and soul. Starting once again with works from the exhibition New Man, one is to come back to the full-length portrait of Good Hunter No.12, or the half-length Good Hunter No.16 as an example in which the face is most clearly depicted. In other words, moments where the soul and its immediate externalisation is concerned. We come back to the smile (pneumatic muscles hydraulic smiles): however enigmatic and indecipherable are the smiles (who understands a 15-years-old boy’s smile anyway?), it is unmistakable that in these paintings and a number of others, the faces and facial expressions do not evaporate, are quite solid, do not easily melt into air. They are unambiguous, reassuring exits through which a viewer can release her gaze, after an assiduously organised bodily trip. One’s stare can finally stop lingering, after the face. On the other hand, many paintings on view in New Man determine or undermine the tone of the facial exhibition by burying the face (Good Hunter – Duplicate No.1, 2022); turning it aback (Good Hunter No.19, 2022 and Good Hunter No.20, 2022); rendering it light and almost feature-less (Good Hunter – Duplicate No.2, 2022); obscuring and shadowing it totally (Good Hunter – Duplicate No.3, 2022 and Good Hunter No.17, 2022); diluting it as heavily as the squelchy body (Good Hunter No.18, 2022); or by simply scooping a hole out of it (Auto Man No.1, 2021, Auto Man No.6, 2020, and Auto Man No.7, 2020).

Roughly in line with Zhang Jiarong’s 2021 essay on Shang Liang’s Mortal at the Helm exhibition, which argues that the artist’s super-buff characters have transcended Hegelian “spirit is a bone,” we observe from a relatively different standpoint that the artist’s concern with the body-soul unity has been positively complicated in recent years, because, first and foremost, the faces are largely, and in different ways, absent, and it was not the case some years ago. After examining recent paintings from New Man as we just did, revisiting earlier works as Tomás Pinheiro did in 2019 (not matching the lucidity of the concise article) shall give us a better sense of Shang Liang’s trajectory from being focused on revealing interiority, to rendering inexpressiveness, depicting a body that is firmly and already vacuous, uncontaminated by significations that are facial, spiritual or soulful in nature.

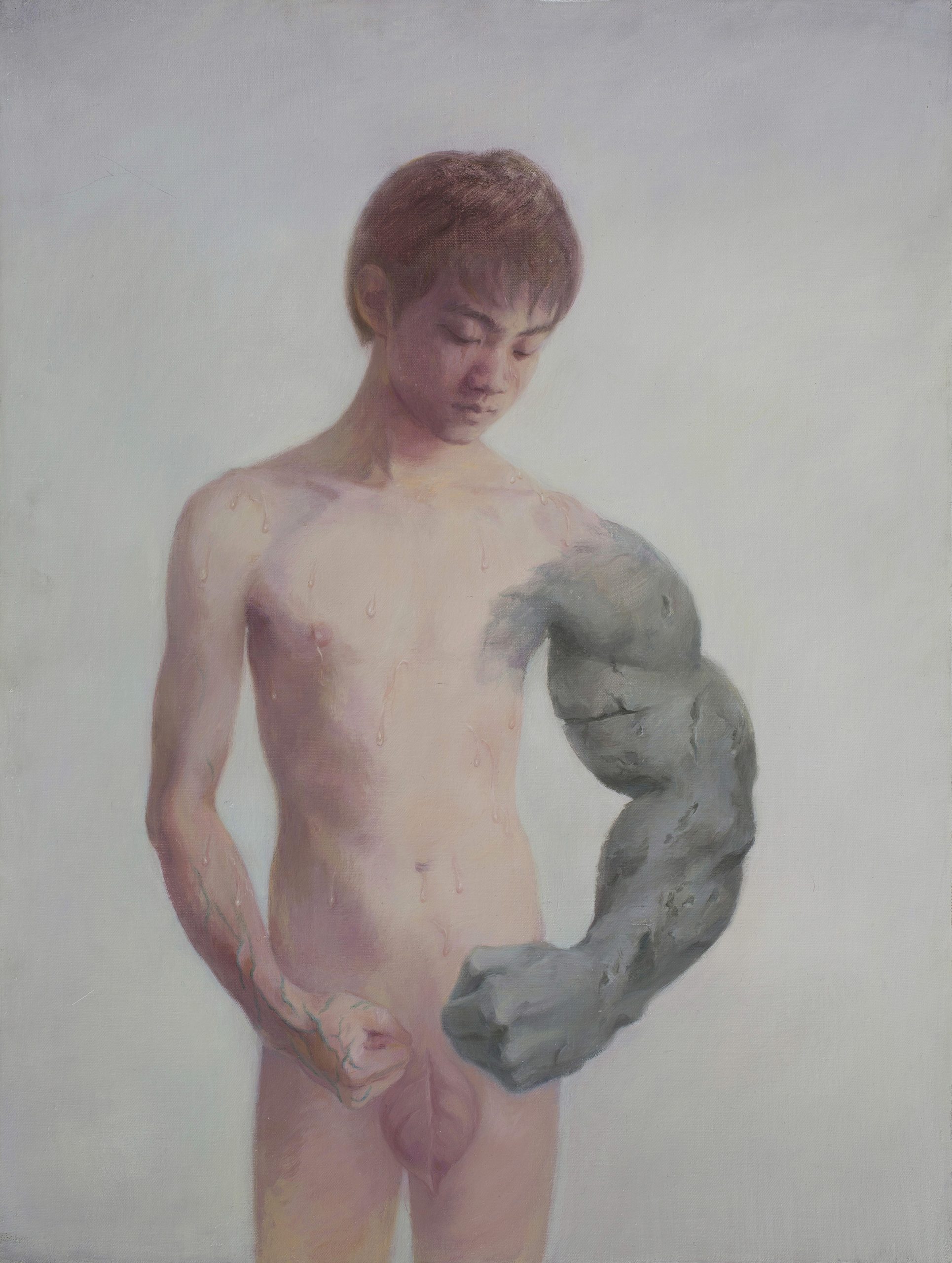

According to the comprehensive yet selective chronology on Shang Liang’s website, although Shang Liang has been creating paintings since at least 2004, the starting point of her artistic career is The Real Boy No.1 (2012), which is modest in size (60 x 80 cm) when compared to recent works. A couple of things about this painting demonstrate how far Shang Liang has come in the last decade or two. It is a largely realistic depiction of a naked young man, with nothing but a fig leaf on his body—it is, incidentally, also what the modern world’s first bodybuilder Eugene Sandow occasionally wore on stage in order to accentuate the perfection of his body—concealing his genitals (or is it what his genitals are? It seems very organic an attachment, if not an appendix). A slender young man, adorned with translucent drops of sweat—another important aspect missing in the recent paintings, besides body hair—trying to squeeze what little muscles he has at his juvenile disposal, while staring down at the left arm, that is in the process of being completely petrified. What is life-like and real about this painting is obviously the overall colour and specifically the skin tone: against an identifiable light source that casts shades here and there, highlighting the muscles that are barely there (yet), the human figure is convincingly skinned, even revealing tonal contrasts, as shown by the blue vessels-crawling right forearm, popping vascularity.

This early portrait of a Tetsuo Shima-like boy is concerned with, instead of grafting an age-less face/head onto a tumorous body, grounding a fantastical plot in an overall realistic, naturalistic pictorial narrative that gradually unfolds. In other words, not only are there matching emphases on both the body and the soul, the separation here is also not clear-cut, but is contagious and therefore procedural, linear, rendering the part-whole relationship natural. The treatment is careful and not as expressive, spending time and exacting effort on facial details, presenting an interesting visual myth: his body becomes petrified as the young boy stares at it, the magic of which reveals his Gorgon identity (there has to be, of course, an eye or two on the body, meeting such stare). Essentially, it appears to be a careful depiction of adolescent metamorphosis if not dysmorphia, establishing the subjective and temporal foundation upon which later works would develop—it is going to be the visual chronicle of the young man’s growth. Other works from the same series are similar, dealing with different aspects and stages of puberty: a young boy who cannot control the growth of beastly hair coming out of his shirt (The Real Boy No.5, 2013); another man who is helplessly growing a pumped, dangerously reddened chest (The Real Boy No.7, 2014); and finally, as the series arrives at a conclusion, a contented, head-rushed young man in The Real Boy No.20 (2016), carrying full-grown, maturated muscles along with a hard-earned smirk, the same smirk that we also see in recent paintings.

It is also important to point out that Shang Liang rather deliberately considers decontextualisation an important compositional strategy for The Real Boy series (that in fact makes its very first appearance in a small series of watercolours in 2011). Early oil on canvas works including the careful 夏天 (2004), a number of expressive 爸爸和狗 paintings (2004), and the darkened, claustrophobic The reflection of a lie (2008) are all attentive to the context in which the characters are caught, conveying messages that are, albeit no less multilayered in meaning, informative and enriched. The three Don’t tell paintings (2008) even explicitly ground erotic, sexual adolescent acts and plays in tangibly mundane environments, narrating very universal (Chinese), relatable intimate stories: a bush in a park, a public toilet, and a classroom-like interior space.

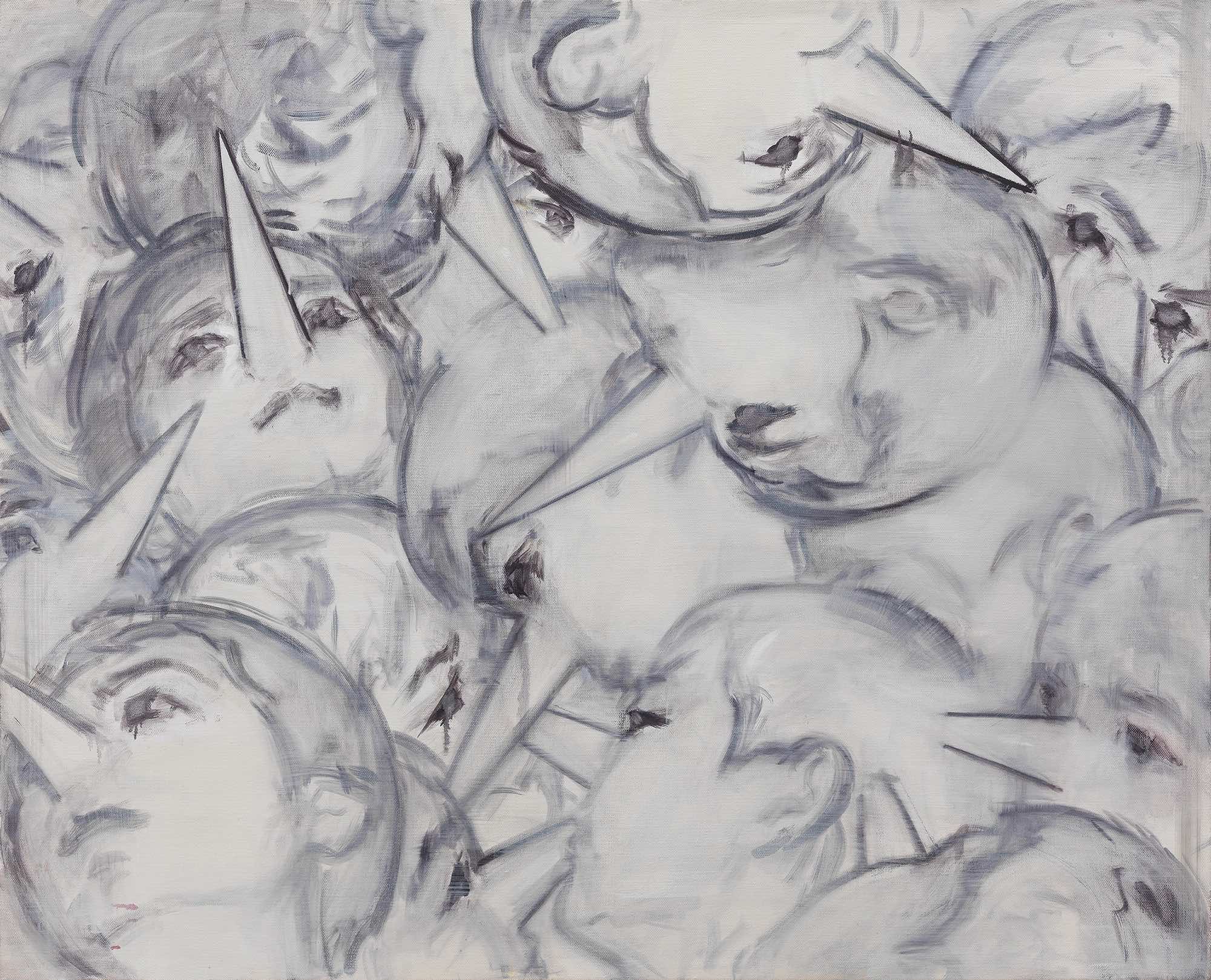

This limited comparison above between recent and early series tries to show that changes in Shang Liang’s art have been clearly visible. Most pertinently, the artist did take greater interest in the face of the isolated, lonely young man (only when reincarnated as a sofa in recent times did he meet peer bodybuilders, embracing one another), as an important way to delineate the spiritual dimension of the figure, and to delineate time. There is also another series of paintings from 2014 to 2017, also titled The Real Boy, that somehow goes astray. The most prominent particularity of these some fifteen paintings is indeed the focus on the face that turns Pinocchio with a long, sharp nose. The artist was apparently obsessed with producing faces at the time, so much so that she repeats the composition of crowding the canvas with numerous heads in The Real Boy No.10 (2015) and The Real Boy No.26 (2016), and even makes a number of paintings based on details of the two, further theatricalising the individual faces, probing, penetrating and nose-fencing with one another.

Shang Liang’s recent paintings, as we were saying, are not as interested in the face. One can discern the start of Shang Liang’s disinterest in the face, in following series such as D520C (2016), and the no-less mysterious Disorder Kind (2017). The former effortlessly turns the young man into a superhuman (American or Soviet alike) kind of pattern, no longer an individual but a conveniently manufactured product that is caught in strange modern-cosmic-architectural scenes. Disorder Kind directly turns sketches and studies into oil paintings, featuring leftovers of silhouettes and seemingly casual gestures. The most astonishing painting from this period is probably D520C No.1 (2016), which is only 40 by 40 centimetres in size. Not only is the young man totally and surprisingly absent here in the skinny geography of stitched lines, the wide-open, awestruck crimson eye is even accompanied by an exceptional portrait of a clearly defined woman.

Back to the paintings from the New Man exhibition, we are now better informed to point out that bodily expressions are ostensibly prioritised. As soon as physical and mental maturation have taken place, as soon as adolescence has concluded, time, especially facial time, stops; what grows and keeps on growing limitlessly is now the body.

III.

Why are you doing this? What are you trying to prove?

(Question asked of Lucie, bodybuilder of eight years, by her mother)

Why do you want to look like a man?

(Question asked of Rachel, bodybuilder of two years, by a work colleague)

She looks so unfeminine and unladylike . . . Her walk is slow and pronounced, she even walks like a man . . . I don’t like it, I don’t like it at all.

(A mother talking about her daughter, Christine, a bodybuilder of five years)

Bodybuilding competitions are disgusting. Those women are sick, disgusting, repulsive.

(Comment directed to Debbie, a bodybuilder of seven and a half years, by her father)

Tanya Bunsell and Chris Shilling, Outside and Inside the Gym: Exploring the Identity of the Female Bodybuilder

Dimitris Liokaftos in A Genealogy of Male Bodybuilding: From Classical to Freaky: “…bodybuilders themselves habitually use the term ‘freak’ or ‘monster’ to speak of each other. Here, though, the spirit is one of attribution of respect and admiration not only for what one looks like but also, and equally importantly, what they had to do to achieve it.”[7] While it is perhaps apt to describe bodies in Shang Liang’s New Man exhibition as freaky, superhumanly and excessively built, our discussion here is just as concerned with the time needed for a pose as such to be possible, “what they had to do to achieve it,” and how the body in the recent works overshadows the face. Also stressing the importance of time well spent in the gym, Adam Locks in his introduction to Critical Readings in Bodybuilding: “It’s probably fair to say that bodybuilding would likely never have achieved the success it did if it had not been for photography – a body-builder might hold a pose for a few seconds, but the photograph held the pose forever… Furthermore, it is important to consider what both the actual bodies and the images of bodies reveal in terms of the inscription of the effort in the gym which has made the body what it is.”[8] Shang Liang’s paintings in the New Man exhibition are focused on, among other lacks, a lack of time, one that renders the freaky bodies magical, skipping the time needed for training and exercising. A representation that is not as veracious as photography, but is almost just as independent and self-sufficient. So independent and self-sufficient, that the emotionless, expressionless face is to be hollowed.

In Sofa Man No.7 (2020) one sees a particularly interesting hollow. Adam Geczy in The Artificial Body in Fashion and Art: Marionettes, Models and Mannequins: “The Olympics did much to turn attitudes and actions to the age of Periclean Athens where nakedness was a sign of strength as opposed to vulnerability or weakness; it was also a mark of civilization.”[9] Besides a few interesting exceptions, Shang Liang’s figures are, as we have mentioned, mostly naked. This nakedness is surprisingly sabotaged in Sofa Man No.7, which is, as straightforwardly announced in the title, a picture that anticipates the arrival of pieces such as Sofa Man No.9 (2022), a sculpture that is in fact a hardened sofa. But it sabotages the nakedness by becoming plaided; the leg-less, more-classical-than-freaky flexing body is thoroughly covered by plaid, leaving only the face an empty hole. This body, unlike other bodies that stand still unnaturally, is ostensibly emotive, clenching the thighs as the man holds his arms behind his airhead. It is about flexing the muscles, as much as about striking a submissive, surrendering pose. One is to even imagine him kneeling, targeted as he is by the cross hairs.

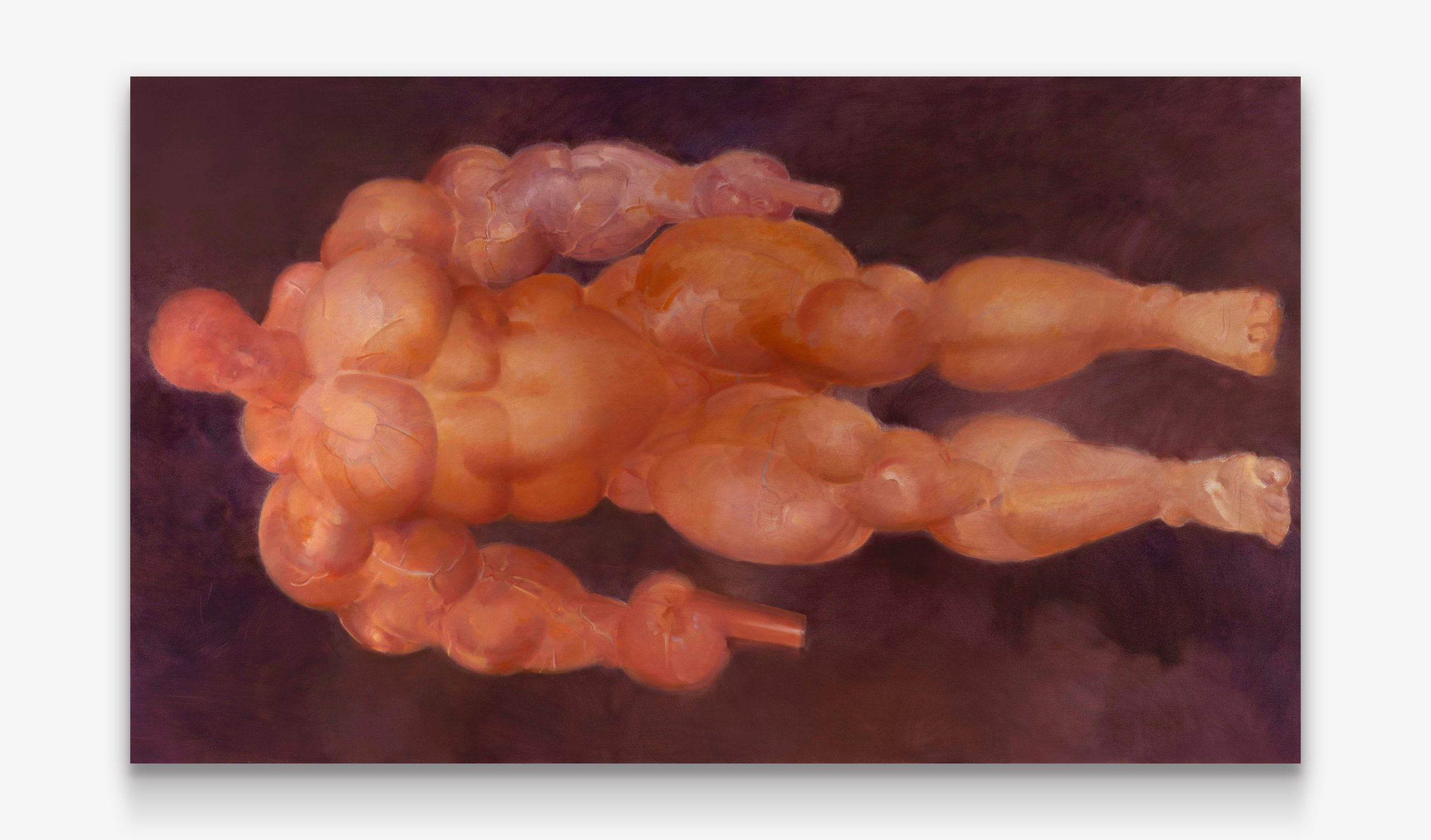

Another face-hollowed painting from the same series and perhaps the most erotic of them all, Sofa Man No.8 (2022), cleverly evades the problem of having to depict a sofa’s genitals (we have later learned that for sculptures such as Sofa Man No.9 made in 2022 there are just no genitals neither) by flipping it over, staging a rather uncanny fall. Uncanny and natural, because although the sofa in the painting is much shorter than the sculptural version of it in Sofa Man No.9 it is not supposed to topple like this. The base is obviously much heavier than the head, and this fact is even accentuated by the contrast in tone: the hollowed face of the sofa is much lighter and brighter than the stuffed bottom of it. The latter is so darkened, as if the movement is so abrupt and unexpected that the lights in the (presumably domestic) environment have yet managed to catch up. What Sofa Man No.9 turns out to be is a manual on how to put the muscle in good use: tripping, overturning itself. Through new, and peculiar compositions like these, one may reconsider paintings like Good Hunter No.17, No.18, No.19, and No.20, that in a more conventional way features inexpressiveness, lack of character and even lack of motion. Along with a sur-ficial intense emphasis on the blurred, hazy, oily, fleshy or metallic texture, then, is a bodily outcome that results from the rather brutal marriage of time (body) and no-time (face), cancelling and at once reconciling with one another.

What we have been trying to address in this essay, has been what renders Shang Liang’s recent paintings, grouped under the banner New Man, uncanny. Particularly, in relation to the different times of the face and the body at work on the surface, we mean to find out why, as the artist’s gesture becomes more expressive in recent times, the subject becomes deader, more doll-like, reversing a Pinocchio narrative—the real boy becomes the doll now. In a couple of recent works that stress a kind of humour, Shang Liang offers new and interesting alternatives that positively break our attempt to contain the trajectory of her oeuvre: the two 青年男子点穴图 (2020) casually sabotage the meaningfulness of reading Good Hunter No.12 and Good Hunter No.13 as they are; they are rigidly bodied with a frozen smile on their faces, because they are maps of acupuncture points—in other words, maps of Chinese anatomy—that have to assume a (pseudo-)scientific look, giving in expressiveness for the sake of accuracy and clarity. Formal and thematic hilarity in The Split Self No.1 and The Split Self No.2 mentioned only in passing above also cracks something open, revealing that, behind the teeth, a cavity that consists of the interior of an inanimate object as a receiver is also formed by fleshy muscles, through and through. The body and soul unity is, after all, largely irrelevant a question. Lastly, we are to suspect that, besides insisting on the placeholder role of the head-face—that is, replacing it with anything ranging from a glove to a hole while insisting that it is there—other new developments in the New Man exhibition also partially or totally returns Shang Liang’s art to a realm that promises tangible danger and death, acknowledging the finiteness and fragility of the body that turns freaky. Thinking once again about Harayway’s “we are all cyborgs” through Geczy, what is a car, if not, like a sofa, something that is a part of me like a muscle?

[1] Buchloh, p.54

[2] Mosse, p.3

[3] Mosse, p.5

[4] Mosse, p.40

[5] Mosse, p.67

[6] Scheller, https://www.frieze.com/article/are-bodybuilders-contemporary-artists

[7] Liokaftos, p.1

[8] Locks, p.5

[9] Geczy, p.108

Included in Shang Liang: New Man (exhibition catalogue, 2024)